A street corner butsudan confirmed that we were not lost in the dark in Japan.

The taxi driver had just dropped us off in front of a stylish two-story house in northern Kyoto that I assumed matched the address we had provided. But when I rang the buzzer and inquired about “Daniel Kelly?” and the lady of the house responded at the gate with a puzzled look, we began to wonder where we really were.

Slowly shaking her head, she kept repeating the phrase wakarimasen . . .

Wakarimasen! Of course! Nothing lost in translation here! Wakarimasen was the one of the 25 Japanese phrases in which I was fluent. She was saying, “I don’t understand.”

I responded with an apologetic gomenasai, as my husband and I turned away.

Don was concerned because we were standing in the darkness—clearly in the wrong place, and the taxi was long gone.

“Wait,” I said. “We have to look for something I saw on Google Street View when I looked up Kelly’s studio.”

In Japan, addresses are not at all clear. Often referred to as “blocks of confusion,” even the locals need maps to find their way around. There are eight components to a Japanese address—and I won’t go into them all—but suffice it to say that even our veteran taxi driver referred to his phone and a “map-app” to get us to Daniel Kelly’s studio.

Don and I took a few steps in the darkness over to a nearby intersection and he used his flashlight to shine a light on what I was looking for—a mysterious shrine enclosed in what looked like a telephone booth with bars. There it was! This is what I saw on Google Street View. A Buddhist shrine—a butsudan. We couldn’t be far from the studio of world-famous artist Daniel Kelly.

We walked in the opposite direction from where we had been dropped off, but didn’t know what to do.

A small white pickup truck drove towards us. The driver had a questioning look on his face. Why wouldn’t he? We were standing in his driveway!

But he knew who we were looking for, and helped us! Domo arigato!

Instead of asking for Daniel Kelly, I should have been asking for the gaijin. Everyone knew him that way. He was the gaijin . . . the foreigner . . . of course! Daniel Kelly was the gaijin-artist who came to Kyoto in 1977.

Born in Idaho, and raised in Montana, Kelly grew up helping in his father’s ceramic tile and marble business. When he entered college, Kelly decided to pursue a degree in psychology, but after helping some friends set up a stained-glass studio, he realized that art was where his interests and talent would flourish. He graduated from college and moved to San Francisco in 1971 to study figurative drawing with expressionist artist Mort Levin.

And as is so often the case, there was a woman involved in another life-changing event. Daniel Kelly met her in San Francisco. She came from Kyoto. When she returned to Japan, Kelly followed her.

Living in Kyoto, Kelly tracked down the studio of Kyoto’s best woodblock print artist, Tomikichiro Tokuriki, a twelfth-generation woodblock printer who offered to take him on as a student, teaching him the basics of woodblock printing and suibokuga Japanese ink painting.

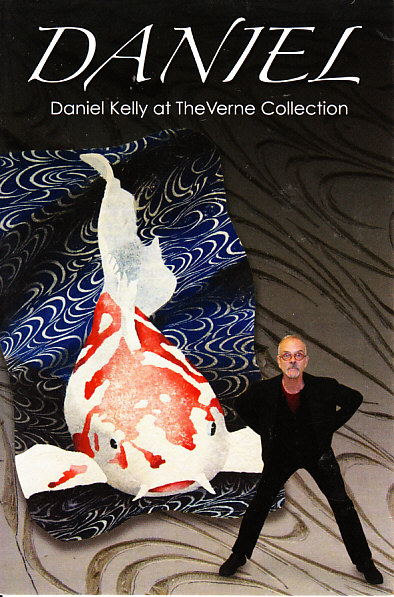

I first discovered world-famous artist Daniel Kelly when I ventured into The Verne Gallery in the “Little Italy” neighborhood in Cleveland, Ohio. It was there that I bought the book Quiet Elegance: Japan Through the Eyes of Nine American Artists, written by Michael Verne and his sister Betsy Franco.

Daniel Kelly’s art intrigued me . . . especially his striking koi themes . . . but it was one of his early creations that held a special appeal—a long horizontal woodblock print called “Buttercups” depicting a row of schoolchildren walking in the rain and carrying yellow umbrellas.

Kelly held his first showing at the Hankyu Department Store in Osaka in 1978, where his collection of misty rain-drenched landscapes, including “Buttercups” sold out. Another of those gaijin artistes working in Japan who was profiled in the book—Sarah Brayer—celebrated Kelly’s success by proclaiming, “You’re not even dead yet!”

Bold moves pay off! While in New York, Kelly showed some of his woodblock prints to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and “Buttercups” was bought by the curators and is now part of their permanent collection.

Kelly’s working much larger now. He incorporates kimono fabric, tatami matting, wooden lids, and fans into his work, placing them against three-dimensional backgrounds of Nepalese paper on wood panels. Sometimes he uses hand-inked pages from Edo-period handwritten books featuring kanji lettering for backgrounds.

His huge masterpiece “Pillow Talk” is one of several koi-themed creations dedicated to the disastrous 2011 earthquake and tsunami in the Tohoku region of Japan.

Finally in the right place, Kelly invited us to join him and his studio assistant and model, the lovely Tomomi Matsuzuki at a large table in what appeared to be his studio/living area. I explained that I had been reading about him and became fascinated with his art—especially the koi themes.

Pouring a glass of wine for me and offering a can of Yebisu beer to Don, I told Kelly how I had missed his reception at the Verne Gallery earlier in the year, and when Michael Verne learned that my husband and I were going to be visiting Kyoto, he told me to “Go and find him in his studio!”

So I did! I explained how I came to be in Japan and that my interest stemmed from my days as an army brat living on Okinawa with my family back in the 1960s.

“My brother was a military brat,” volunteered Kelly. “The stories he told me when I was young, about living in Japan probably inspired me to end up here.”

I wondered about that statement—but before I could ask, Kelly cleared things up, adding that his brother was actually a half-brother—and that his family was a “modern family” before we knew it as a popular term. It sounds like there were at least three marriages for his mom and dad. It could only be a bigger story, but not the one I was trying to put together.

Great art challenges the rules. And Kelly is one who definitely challenges the rules.

A huge creation was propped against the opposite wall—with wooden support strips behind it for ease in transport. “Little Giant,” a fish-eye lens portrait of Tomomi, had been exhibited in Tokyo at a weekend show and had been acquired by someone in Melbourne. SOLD! Soon to be packed and crated.

Just a week before the exhibition Tomomi posted on Facebook that “Daniel stayed up all night!”

We all laughed.

I got it. I totally got it! Kelly and I were in agreement that yes, we creative souls do find ourselves staying up late or even all night long . . . while drinking wine. The solitude of late night hours only boosts creativity.

My cell phone went off and I picked up, answering authentically—as I had planned.

“Moshi, moshi , , , hai . . . dozo!”

Like I knew what I was saying! But it sounded convincing to our son and his radio audience.

“Boy-san” was back at home in Cleveland, broadcasting live on college radio station WRUW-FM 91.1. Paul had planned to phone us using the free LINE app and put me live on-air to talk about what we were doing in Japan!

Anyway, Paul’s previous calls to us in Japan had not worked out well. We often were somewhere too noisy to talk, but this time he caught us at Daniel Kelly’s studio. This time we could talk. Even Kelly could talk.

Leading up to the big overseas phone call, Paul had been playing selections by “Shonen Knife,” a female-fronted Japanese punk rock band as a lead-in, telling his “drive-time” audience that he would be calling somebody in Japan—namely his parental units . . . to find out what they were up to 14 hours into the future.

I told him that we were now in Kyoto, and at the studio of a world famous artist with a Cleveland connection to a gallery in the Little Italy neighborhood.

“Do you want to speak to Daniel Kelly?”

I handed my phone over to Kelly, expecting him to say a few words to his art-fans in Cleveland, but Kelly was speaking way too fast and getting into something about the current state of academics in America. I can’t quite remember all that he said, but it was not what I expected.

(And even later when I caught up with Paul, he told me that Kelly was speaking so rapidly that he was breaking up over the LINE app. Only every other word could be heard. Someone did phone in to the station to say that he had been to The Verne Gallery and knew Kelly’s art, but by that time Kelly was no longer on the phone, so all Paul could say was, “Thanks for calling. I’ll let him know.”)

All of a sudden Kelly proclaimed that he was hungry!

Were we hungry? We should all go out to dinner!

We followed Kelly and Tomomi out of the studio and down the street to a neighborhood sushi-counter restaurant with about eight stools and several small tables. Every counter seat was taken and we squeezed into a small table for four. Tomomi took charge, ordering what she thought we would like—she was right!

Don and I didn’t really know what we were eating, but it was authentic and delicious! We continued to drink . . . but now from large bottles of Asahi beer . . . Kampai!

Getting fuzzy, all I can recall was miso soup and a mushroom perched atop a pillow of sushi rice. Don remembers raw salmon . . . and then barbequed salmon . . . we were eating like locals—Anthony Bourdain would approve!

The sushi-chef behind the counter surfaced every now and then to see how we were doing, while a lady who was most likely his wife, kept changing the tiny dishes with new delicacies. It was like we had found an undiscovered sushi-joint in “Parts Unknown” and for now I will call our chef, “Masa-san.”

Kelly observed our feeble use of chopsticks and instructed us in the easiest way to handle them, but it didn’t help much. Don and I are still working on our chopsticks prowess. We will never give up. We can only get better . . . way better.

Kelly asked someone to call for a taxi to take us back to our hotel while he and I split the check. I pulled a 10,000 Yen note out of my saifu for our share. It was after I had drunk quite a few glasses of Asahi and I can’t remember for certain. It must have been 10,000 . . . I was feeling fuzzy, but it couldn’t have been 100,000 Yen.

At least in Japan, there is no tipping . . . no tipping!

Daniel Kelly and I have several things in common: keeping late hours while drinking Costco wine and blasting music to fuel our creativity!

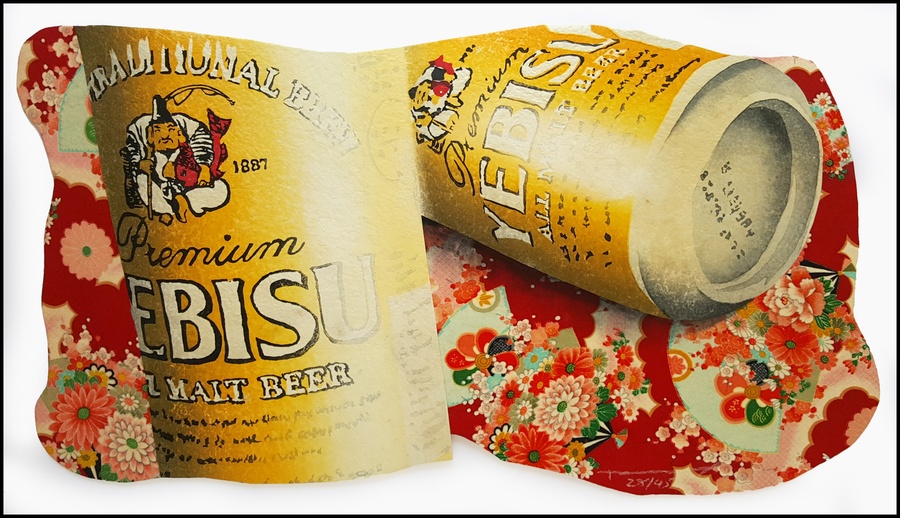

After I returned home, I stopped by The Verne Gallery to update world famous art dealer Michael Verne about our visit to Kelly. I looked around the gallery at all the original Kelly pieces now with a greater appreciation. And then my eyes settled upon a small woodblock print on the floor. Two empty cans of Yebisu had been tossed against a kimono fabric background . . .

“I know that beer,” I exclaimed. “We drank that beer.”

“But why is this print called ‘Dead Soldiers’?”

Verne explained the meaning of the title to me, and later my husband confirmed it.

Empty beer cans—dead soldiers.

I get it. And I can just picture Kelly tossing those empty cans aside and then turning them into art.